Tim Squirrell: Why Free Speech isn’t absolute and it’s okay to be vulnerable

The cancellation of a public debate in Oxford on the topic “This House believes Britain’s abortion culture hurts us all” caused a controversial and emotional debate in the United Kingdom. After Tim Squirrell, current president of the Cambridge Union Society, published an article in the students’ newspaper “The Tab,” saying, “it’s about time we recognised that and started thinking responsibly and considerately about freedom of speech,” he was exposed to hostilities. Tim allowed us to republish his latest article from his blog “Squirrelling the Motion” that reflects on the ongoing discussion. Besides offering an overview on the events of the last week, it discusses some ideas on what debate should or should not be.

I don’t really mind if you read this, it’s mainly for my own peace of mind following an interesting week. I don’t think I’ve ever had quite so many people send me hate over the internet – I’ve been called everything from a “bell” and a “dickhead” to ‘moronic’ and a “patronising snob,” I’ve had an article in a student newspaper call for my expulsion, and the better half of a hundred copies of The Spectator sent to my work address, sporting a cover story on the “new enemies of free speech.” If I’m honest, I’ve mostly found it all quite amusing – I think there was only one point at which the whole thing got a little too much and started to upset me, but I started learning a while ago that you just can’t take anonymous comments too seriously.

What happened?

So I thought I’d recap what happened, and then chat a bit about where I think we went wrong. This week there was going to be a debate in Christ Church, Oxford. For those unfamiliar with the idiosyncrasies of Oxbridge, they are collegiate universities – that is, when you go to study there, you are put into a college, which is where you eat, sleep, socialise, have pastoral and academic support etc. The debate was to be run by an organisation called Oxford Students for Life (OSFL), and the motion was “This House believes Britain’s abortion culture hurts us all.” There were two speakers, Tim Stanley and Brendan O’Neill, both quite prominent journalists.

When the JCR (Junior Combination Room – essentially the elected representatives of the student body of a college) got wind of the event, they lobbied the college to reconsider holding it, on the basis of the threat to the emotional and mental wellbeing and safety of the students of the college. A couple of other groups in Oxford, including an ad hoc event set up entitled “What the fuck is ‘Abortion Culture’?,” said they would turn up and protest. The college decided that there was not enough time to adequately address the safety concerns, and therefore decided the event would not go ahead in their premises. OSFL attempted and failed to find another venue at short notice, and so the debate did not happen.

When the JCR (Junior Combination Room – essentially the elected representatives of the student body of a college) got wind of the event, they lobbied the college to reconsider holding it, on the basis of the threat to the emotional and mental wellbeing and safety of the students of the college. A couple of other groups in Oxford, including an ad hoc event set up entitled “What the fuck is ‘Abortion Culture’?,” said they would turn up and protest. The college decided that there was not enough time to adequately address the safety concerns, and therefore decided the event would not go ahead in their premises. OSFL attempted and failed to find another venue at short notice, and so the debate did not happen.

Ironically enough, this was, on the college’s end, nothing to do with protecting student welfare. The reason they didn’t allow the debate to go ahead was, I was informed last night by a Christ Church student, because the college requires rooms to be booked three days in advance, and OSFL left it until two days before their debate to do it, meaning that what was seen as an excuse – “not enough time to address safety concerns” – was actually college bureaucracy in action. In her article for the Independent, Niamh McIntyre gives a better explanation of this.

Regardless of exactly why the college shut it down, the result was that both Tim Stanley and Brendan O’Neill were very unhappy. Tim published an article in the Telegraph saying that “Free speech is under assault on campus,” and Brendan O’Neill wrote a leader article for The Spectator called “The Stepford Students,” which referred to his opposers as “the new enemies of free speech.” A number of people, myself included, noted the irony in their claim that their free speech was being suppressed coming from articles in the national press. Neither Tim nor Brendan appeared to appreciate the joke.

My role in this little fracas came in two parts: first a twitter spat, then an article. Beware when clicking the first link – reading the entirety of a twitter argument can be both incredibly time-consuming and harmful to your sanity. Essentially I tweeted some criticism of Tim Stanley’s article, and then various people got upset at this because I’m currently the President of the Cambridge Union, a debating society which has the slogan “promoting free speech and the art of debating.”

As a person in this position, the argument went, I ought to believe in absolute freedom of speech, and not try to shut down any kind of debate. To me this seemed interesting and possibly counterintuitive – I think that a person in my position has to think critically about what exactly free speech consists in within any given circumstance, and what it really means to give somebody a platform, either as an individual or in a debate. Over the course of the two-or-so years I’ve spent working at the Union, I’ve thought an awful lot about our role in facilitating debate, in running events which are controversial enough that people want to come but without being irresponsible in their subject matter, their framing or the speakers invited. As a society with limited resources – time, money, and most importantly student attendance – we have to consider carefully what debates we’re going to hold each term, who we’re going to invite to them, and how we want to run them.

My article essentially ran along these lines. I said that there are some limits to freedom of speech, without prescribing what they are in any given instance, but listing five factors which need to be taken into account and weighed up when setting up any kind of debate: what might be said, who is speaking, where it takes place, what the subject is and how it’s framed.

This, to me, didn’t seem particularly controversial. I also suggested why it might have been that people had objections to the proposed OSFL debate, based on the criteria listed above: there were only two speakers, neither of whom had ever been in possession of a uterus; the debate was taking place in a college which is also home to people who may have had abortions and aren’t particularly comfortable with the idea of this debate going on in their home; and the framing of the motion wasn’t particularly good, assuming the existence of an “abortion culture”. Some people also had a problem with the debate being hosted by a pro-life society.

Again, none of this seemed particularly contentious, but the response was remarkable. If you go into the comments on the Tab article, they are overwhelmingly negative. A lot of people suggested that I didn’t want debates to go ahead if they could offend anyone, or that I was shutting down freedom of speech, or telling people what they can or can’t listen to. I don’t think I was doing any of this. Ultimately I agree with the decision not to host that particular debate in that particular context, but I don’t think any of the criteria I laid out were unfair. Every debate we hold isn’t just an expression of ideas – what is “just a debate” to some people is something which has a very real impact on the lives of others. We don’t just say things in a vacuum, there are very real social contexts and impacts which we ought to take into account when we set up debates.

Where we went wrong

I think we made a tactical error in this whole situation. When Brendan O’Neill and Tim Stanley published their articles, they framed what had happened as a prioritisation of “feelings” over free speech, what they consider to be a fundamental right. We let them frame it this way, and the entire discussion took place on their terms, where we were the brutal oppressors of the new liberal orthodoxy, the foaming-at-the-mouth PC brigade who want to shut down debate and never let anyone be offended by anything.

It’s not about free speech. That was where we went wrong. This whole thing is not in the slightest bit about free speech – that is, the right to say things without fear of the state shutting you down. Freedom of speech is just a legal right, and when you invoke it – to paraphrase xkcd – you’re saying that the most compelling thing that can be said for your position or debate is it’s not literally illegal to say or hold it. There are two things that we are actually talking about here – or rather, which we should be talking about.

The first is what it means to privilege a particular person’s speech. When we give someone a platform, particularly at a prestigious institution like Oxford or Cambridge, we lend a degree of legitimacy to their point of view. Whilst this may not matter if, for example, you’re a high-ranking politician who is legitimised by elections they have won, it does matter for other people. There are an awful lot of people who would love to take part in the debates we hold, but we choose not to invite them to speak for numerous reasons: they’re not an expert with the requisite experience, they don’t have anything particularly interesting to say, or sometimes they just have horrifically offensive opinions which we don’t want to give the privilege of a platform to.

A number of people over the past week have recommended I “read J.S. Mill’s On Liberty,” in order to rectify my views. What they’re thinking of when they say this is an idealised Millian arena, in which all opinions can be presented and challenged, and the bad ones will be refuted and the good ones accepted. The problem is that this arena doesn’t exist. Sometimes the people with the “good” opinions aren’t very good at expressing them. Sometimes people use tricks of rhetoric to get an audience to support their otherwise heinous views.

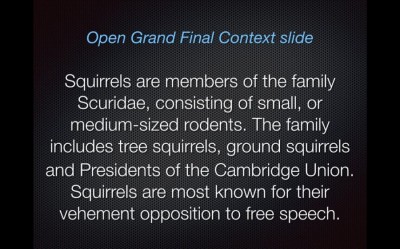

Humorous info slide put up before the final of the Cambridge Intervarsity Debating Competition 2014. © Tim Squirrell

Moreover, debates can have greater capacity to do harm than good. First, there’s the problem of political asymmetry: If, for example, we hold a debate about the repatriation of immigrants, then there is a greater capacity for harm to occur to sometimes vulnerable immigrants if the debate goes against them than there is for any benefit to accrue if the debate goes the other way. It’s far more likely, for example, that the Daily Mail will publish an article entitled “Cambridge students think we should send them back” with the former result than that they will publish anything at all with the latter. Debates like this can play into already existing biases about particular groups of people, often vulnerable people, which the audience hold, in order to make it even harder for them to achieve equal status.

The Liberal Orthodoxy

The second thing this argument should actually be about is the “orthodoxy,” and power, and privilege, and oppression. When Brendan O’Neill and Tim Stanley get to claim, from the pages of national media outlets, that they are being oppressed and their free speech squashed by the new liberal orthodoxy of students, we know something is wrong. They are the orthodoxy. What students do best is to challenge the firmly held beliefs of the generation above them, and that is exactly what we are doing. We are challenging the notion that debates happening in formal contexts have no ramifications past the end of the evening. We are challenging the claims of privileged men to have the right to speak wherever they want, whenever they want, on whatever topic they want.

Finally, we are challenging the idea that all weakness is bad. Brendan O’Neill in particular despises weakness. He is absolutely right that quite a lot of students now want the right to feel comfortable, but he is totally wrong when he says this like it’s a bad thing. Absolutely we should feel comfortable in the places we live and study, in the places we have made our homes. There are some students who are more vulnerable than others, for a whole host of reasons: they may have had emotionally traumatic experiences, they may be suffering from mental illness, they may be from backgrounds which don’t have the privilege of sending people to top universities regularly, they may just be fragile – but that’s okay. We, as students, are beginning to realise that there is more to life than just discussion. We’re beginning to realise that we don’t need to be ashamed of our weaknesses and vulnerabilities. We’re beginning to realise that sometimes we have to prioritise the emotional, mental and physical wellbeing of our friends and colleagues over the ability of privileged people to come in to our homes and say whatever they like.

If that makes me an enemy of free speech, so be it.

Tim Squirrell/ama/hug

The Mittwochs-Feature: every Wednesday at 10 am, the “Wednesday Feature” introduces an idea, a debate, a book or a person. If you want to kick off a debate, send us your proposal via email at team [at] achteminute [dot] de.

Tim Squirrel is the current president of the Cambridge Union Society. He is responsible for organising a programme of debates and overseeing the planning of other events during his term in office. Tim studies Natural Sciences at the University of Cambridge.